Bee (mythology)

Bees have been featured in myth and folklore around the world. Honey has been an important resource for thousands of years, and bees themselves are often characterized as magical or divine creatures.

Worship[edit]

In mythology, the bee, found in Indian, ancient Near East and Aegean cultures, was believed to be the sacred insect that bridged the natural world to the underworld[citation needed].

The bee was an emblem of Potnia, the Minoan-Mycenaean "Mistress", also referred to as "The Pure Mother Bee".[1] Her priestesses received the name of "Melissa" ("bee").[2] In addition, priestesses worshipping Artemis and Demeter were called "bees".[3] Appearing in tomb decorations, Mycenaean tholos tombs were shaped as beehives. The Delphic priestess is often referred to as a bee, and Pindar notes that she remained "the Delphic bee" long after Apollo had usurped the ancient oracle and shrine. "The Delphic priestess in historical times chewed a laurel leaf," Harrison noted, "but when she was a Bee surely she must have sought her inspiration in the honeycomb."[3][4][5]

Myth[edit]

The Homeric Hymn to Apollo acknowledges that Apollo's gift of prophecy first came to him from three bee maidens, usually but doubtfully identified with the Thriae, a trinity of pre-Hellenic Aegean bee goddesses.[6] A series of identical embossed gold plaques were recovered at Camiros in Rhodes;[7] they date from the archaic period of Greek art in the seventh century, but the winged bee goddesses they depict must be far older.[4]

The Kalahari Desert's San people tell of a bee that carried a mantis across a river. The exhausted bee left the mantis on a floating flower but planted a seed in the mantis's body before it died. The seed grew to become the first human.[8]

In Egyptian mythology, bees grew from the tears of the sun god Ra when they landed on the desert sand.[9]

The Baganda people of Uganda hold the legend of Kintu, the first man on earth. Save for his cow, Kintu lived alone. One day he asked permission from Ggulu, who lived in heaven, to marry his daughter Nambi. Ggulu set Kintu on a trial of five tests to pass before he would agree. For his final test Kintu was told to pick Ggulu's own cow from a stretch of cattle. Nambi aided Kintu in the final test by transforming herself into a bee, whispering into his ear to choose the one whose horn she landed upon.[10][11][12]

In Greek mythology, Aristaeus was the god of bee-keeping. After inadvertently causing the death of Eurydice, who stepped upon a snake while fleeing him, her nymph sisters punished him by killing every one of his bees. Witnessing the empty hives where his bees had dwelt, Aristaeus wept and consulted Proteus who advised him to give honor in memory of Eurydice by sacrificing four bulls and four cows. Upon doing so, he let them rot and from their corpses rose bees to fill his empty hives.[10]

According to Hittite mythology, the god of agriculture, Telipinu, went on a rampage and refused to allow anything to grow and animals would not produce offspring. The gods went in search of Telipinu only to fail. Then the goddess Ḫannaḫanna sent forth a bee to bring him back. The bee finds Telipinu, stings him and smears wax upon him. The god grew even angrier and it wasn't until the goddess Kamrusepa (or a mortal priest according to some references) uses a ritual to send his anger to the Underworld.[13]

In Hindu mythology, Parvati was summoned by the Gods to kill the demon Arunasura, who took over the heavens and the three worlds, in the form of Bhramari Devi. To kill Arunasura, she stings him numerous times with the help of innumerable black bees emerging from her body. The Gods were finally able to take control of the heavens and the celestial worlds again.[14] Also, the bowstring on Hindu love god Kamadeva's bow is made of sugarcane, covered in bees.[15]

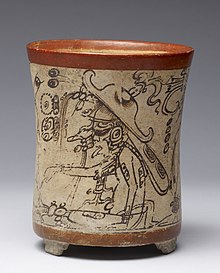

In Mayan mythology, Ah-Muzen-Cab is one of the Maya gods of bees and honey.[16][page needed]

Notes[edit]

- ^ G.W. Elderkin (1939) "The Bee of Artemis"The American Journal of Philology 60 pp. 203–213

- ^ Neustadt, Ernst 1906. De Jove cretico, (dissertation, Berlin). Chapter III "de Melissa dea" discusses bee-goddesses and bee-priestesses in Crete.

- ^ a b Harrison 1922:442.

- ^ a b Cook, Arthur Bernard. "The bee in Greek mythology" 1895 Journal of the Hellenic Society 15 pages 1–24

- ^ Melissa Delphis, according to Pindar's Fourth Pythian Ode, 60.

- ^ Scheinberg, Susan 1979. "The Bee Maidens of the Homeric Hymn to Hermes". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 83(1979), pp. 1–28.

- ^ One was illustrated in a line drawing in Harrison 1922:443, fig 135

- ^ Chrigi-in-Africa. "The First Bushman / San". Gateway Africa. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Norton, Holly (24 May 2017). "Honey, I love you: our 40,000-year relationship with the humble bee". The Guardian.

- ^ a b McLeish, Kenneth (1996). Bloomsbury Dictionary of Myth. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-2502-8.

- ^ "Kintu the Person vs Kintu the Legend". Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ "Kintu – The First Human in Buganda". Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Hoffner, Harry A.; Beckman, Gary M. (1998). Hittite Myths. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. pp. 15–16, 20, 22. ISBN 978-0788504884.

- ^ "The Devi Bhagavatam: The Tenth Book: Chapter 13". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-932476-03-3.

- ^ Milbrath, Susan (1999). Star Gods of the Maya: Astronomy in Art, Folklore, and Calendars. The Linda Schele series in Maya and pre-Columbian studies. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-75225-3. OCLC 40848420.

References[edit]

- Harrison, Jane Ellen, (1903) 1922. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek religion, third edition, pp 91 and 442f.

- Berrens, Dominik (2018): Soziale Insekten in der Antike. Ein Beitrag zu Naturkonzepten in der griechisch-römischen Kultur. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (Hypomnemata 205).

- Engels, David/Nicolaye, Carla (eds.), 2008, "Ille operum custos. Kulturgeschichtliche Beiträge zur antiken Bienensymbolik und ihrer Rezeption", Hildesheim (Georg Olms-press, series Spudasmata 118).

- James W. Johnson, "That Neo-Classical Bee" Journal of the History of Ideas 22.2 (April 1961), pp. 262–266.